Mimo was mad at me. “I can’t believe you stole my driver’s license!” she blurted when she found it amongst my things. She thought she had misplaced it which meant she had to go through the hassle of standing in line at DMV to replace her license.

“Sorry,” I offered. “I should have asked you.”

My own license had been suspended after some high school friends and I were shopping for alcohol. “Let’s try that liquor store,” one of my friends said as we were driving down Route 44 from Salisbury to West Hartford. One of us had a fake ID and we sent him in to make the purchase for our party weekend at my parent’s house while they were in Pakistan. He got a case of the nerves inside the store and returned with only a fifth of vodka. “That’s all you got?” the rest of us said in unison. “There’s six of us. That won’t even be enough for one drink a piece.”

So we stopped at the next liquor store and sent him back in with another friend for support. This time they came out with a case of beer and a large bottle of vodka. We put the unopened booze in the trunk of the car and continued on our way. We were on the road for less than a minute when we heard the sirens and noticed the flashing lights of the police car behind us.

I handed the officer my recently acquired license and registration. He asked to look in the trunk where he found our party supplies. We had to go to the police station where they detained our friends who had purchased the liquor, and allowed the rest of us to go.

I got a ticket for driving underage with alcohol in the car, albeit unopened and in the trunk where it was supposed to be. But I was sixteen and had no business driving with booze in the car.

Shortly after that I got a notice to appear in court. Puchi offered to come with me for moral support, and we agreed to keep this news from Ami and Aba who were still in Pakistan. The morning of the court date Puchi and I woke up and I said, “I’m scared. I don’t want to go to court.”

I had visions of a judge in a black robe. Admonishing me and judging me for my bad behavior. So we blew it off. Next came the notice that my license had been suspended for missing my court date and I was instructed to send it to DMV. “Driving in Connecticut is a privilege granted by the Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles. And, like all privileges, it can be taken away―temporarily or permanently―if you prove yourself unable to follow the rules under which it was granted. Once your license is suspended or revoked, you can face serious criminal penalties if you continue to drive,” the notice said.

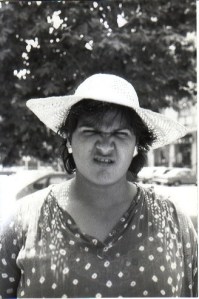

Mimo and I look a lot alike, so I thought I could use her license until my suspension was over. And since she was six years older than me, her license also had the added benefit of functioning as a fake ID should I ever want to purchase alcohol again. When she discovered I had stolen it from her she demanded it back.

“But you have another license,” I said. “You don’t need two. I’ll just use it until I get my license back.”

“No way,” Mimo said, not even considering it for a moment.

When we went to Mimo’s graduation from Ithaca College a few months later, Mimo and Puchi wanted to stay on in Ithaca for the graduation parties, and asked me to drive Ami back to Connecticut. Ami hated driving.

“But I don’t have a license,” I said looking at Mimo. “I wouldn’t want to risk getting stopped without a license,” I added, giving her a bitchy smile. So there, I thought to myself.

“Give Foo your license,” my mother suggested to Mimo, not knowing that I had stolen it a few months earlier and had recently returned it to Mimo.

“You know she can use it for other things than driving,” Mimo said. This from the sister who took me to a bar on my sixteenth birthday. The hypocrisy was confusing me.

“If she wanted to do those other things, she wouldn’t need your license,” Ami said. “She looks old enough.”

Mimo reluctantly handed me her license. This time I got to keep it, thanks to Ami.