My father did not want six children. I think he would have been happy with two. But my mother kept producing healthy babies (even though she smoked through all her pregnancies). Who knows what their birth control situation was, but I don’t think they used any. My mother used to say she would have made a good Catholic woman.

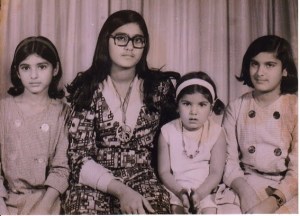

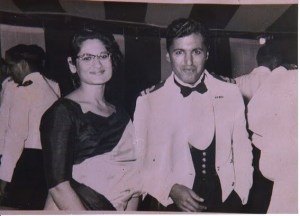

Here’s a picture of my parents, early in their marriage, with their first two children, Baba and Muna. I think the photo was taken in the early 1960s at the Dumlotti farm, outside of Karachi. You can sort of see from the landscape that it is flat and desert like.

When my mother went into labor with me in December of 1967, the doctors thought only one of us would survive, so they asked my father which one of us he wanted to save. And my father replied, without hesitation, “My wife.”

It always made me happy to hear this story recounted. I mean, I’m glad we both made it, and I’m glad to be alive, but I think my father had the right priorities, he wanted to save his wife.

After I was born (a healthy ten pound baby, despite the difficult labor) my father got a vasectomy. There were no pregnancies after me, although I used to ask my mother why she didn’t get pregnant again. I wanted a younger sister or brother to boss around too.

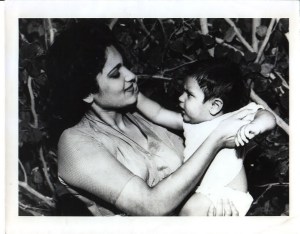

Here we all are. Baba starting us off on the left, about twelve years old, I think, and me at the other end, maybe about six months old.

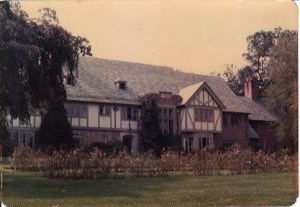

This picture was taken at the Abbottabad house, called Rocky Ridge, pictured here from the back. The gardens were always perfectly manicured.

As I got older, I really appreciated being part of a big family, even though everyone bossed me around. Mostly, I had many observations about my siblings. One of which I shared with my mother in my early twenties when things began to unravel.

“It’s good you didn’t stop with the first two,” I said. By now, Baba’s true colors were pretty much out in the open for anyone to see. The manipulation, the deception, the rage, the greed. And Muna was acting out in inappropriate ways.

Baba and my mother shared a close relationship. They were twenty years apart in age so she relied on him as more than a son in some ways. A confidante and friend. When he suggested that she put the Nathiagali house in his wife’s name for financial reasons, and financial reasons only, she agreed. She trusted him, and he used that trust to build his personal wealth.

My father had passed away by now and left behind some debt. Baba insisted that putting the Nathiagali house in his wife’s name would protect it from the banks which were looking to be repaid for the various business loans my father had taken in order to expand his poultry breeding company.

The Nathiagali house was a place of great joy and happy memories for us all. And my mother always maintained that it would be put back in all our names. My brother betrayed her wishes and her trust. He stole the house from us. He stole the property, but more importantly for me, he stole the experience of the house and the chances of enjoying time there.

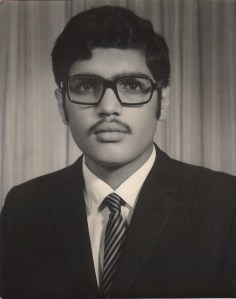

I found this photo of Baba on a cousin’s Facebook page. It’s Baba’s Facebook profile picture. Seems appropriate somehow, given his behavior, to be pictured aiming a rifle.

And Muna, well she began to act strange in the early 1980s. Mainly acting inappropriately to provoke my mother. She started coming down to afternoon tea, a daily ritual, in tattered clothes. We were expected to be dressed well, not in the finest of garments, but neatly. And we were expected to pour tea and offer cakes and cookies to whichever guests had stopped by that day. Muna, to my mother’s horror would slump down on the sofa, in a passive aggressive defiance.

Once at a dinner party that Muna asked my mother to arrange so that she could meet an eligible suitor and his family, she shocked everyone when she said, “marriage is a form of prostitution.” It was embarrassing.

That is not to say each of us did not bring pain into the family. We did. But in many ways, the younger lot embodied my parents values in a way that my older siblings did not, and still do not. Which is why I think it was fortunate for my parents that my mother did not stop at two, otherwise they would not have experienced the joy that the rest of us brought to the family.

Muna cannot really be blamed for her behavior since she is bipolar, and has never really been given the proper medical care. But Baba has much to answer for and much to reconcile. I have to wonder, and I know I am not alone, will he ever do the right thing? Or will he take his wrongdoings to his grave?