When Mimo and Seamus got engaged, I asked her, “How did Seamus propose to you?”

“Oh, you know,” she said “He just proposed.”

“I want the details,” I replied. “Were you out to dinner? Was it romantic? Were you drinking champagne? What were you wearing?”

“Well, actually,” she said, “It wasn’t really like that.” Apparently the “engagement” happened sort of by accident. Mimo wanted to take Seamus on a short vacation to Shangrila, a resort in the northern areas of Pakistan started by my uncle, one of my father’s older brothers, Brigadier Aslam Khan, and now owned by one of his sons. Shangrila is nestled amongst the Karakorum mountain range in Skardu, which is the main town of the Baltistan region in the Skardu Valley, at the confluence of the Indus River near the border of Tibet.

My uncle had owned the land for many years. At some point, maybe in the 1950s, I’m not quite sure, a plane crashed onto the property and instead of having the wreckage removed, he moved the plane to a more desirable location on the property, by a lake, and refurbished it into a small cabin where he would take his young family for holidays. In later years he built the resort around the plane, with self-standing cottages surrounding the lake. The extended family loved going there for holidays in the summer.

Shangrila

When Mimo called to make a reservation for a romantic getaway for her and Seamus, she said, “I’d like to reserve a cottage for my fiancée and me.” Seamus had not actually proposed, but Mimo thought it would be more acceptable for them to share a cottage if she called Seamus her fiancée. Seemed like a good idea. That is, until my entire extended family started calling her to congratulate her on her engagement.

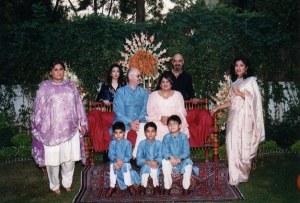

We have a large extended family. Last time I counted, we had about 60 first cousins. And word travels fast through this mostly close-knit family. So when the news got out about her “engagement” Mimo thought she better follow through with it, and she organized an elaborate engagement party, with custom-made outfits, jewelry, and a dais for the happy couple.

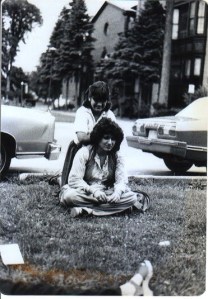

The engagement party.

Seamus, good-natured as he is, went along with the plan. Mimo picked out an emerald and gold engagement ring and wedding band, and told the family that the engagement party would be the only function in Pakistan since they had friends and family in the US and in Ireland. So the family assumed that she got married sometime shortly after the engagement party.

The truth is they could not get married right away because Seamus was in the process of getting a divorce from his first wife, and in Ireland a divorce typically takes five years. Mimo asked us sisters to be discreet about this fact, and loyal as we are to each other, we were vague when asked about the details of her wedding. After all, I knew what it was like to be in the closet, so I honored her wishes and kept my mouth shut.

They’ve been a happy, devoted couple ever since. They did finally seal their union, brought about somewhat abruptly by some immigration issues Mimo was having because they were not legally married. They got their marriage license from the Norwalk County Court House, near our house in Long Beach. The Justice of the Peace had trouble pronouncing their names, stumbling over Fazilet and pronouncing Seamus, “Seemouse.” Her good friends Lulu, Peter, and Edward flew in from London, Massachusetts, and Florida and we had a small celebration afterward. Prior to this legal recognition of their relationship, Mimo and I had something in common: neither of our relationships was recognized by the state.

The happy couple

I wouldn’t even be blogging about this, since I thought we were still supposed to be discreet about this series of events. But Mimo emailed me yesterday to tell me how much she was enjoying reading the blog, and I told her I was dying to tell her engagement story, but that I wouldn’t do it without her go ahead.

“Of course you have the go ahead. I am beyond caring what people think,” she wrote. “As Podge and Rodge say, ‘If I could care less, I would.'”

I don’t know who Podge and Rodge are, but I like the way they think.