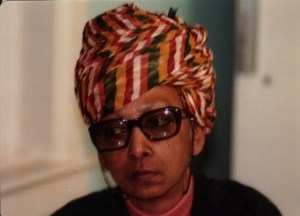

My mother and I were in my parent’s bedroom surveying her closet. She was selecting a sari to wear to Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in 1981.

“Will you take one of those tours of the White House?” I asked.

“I’ll only go to the White House if I’m invited,” she replied. “I’m not going on any public tours,” she said haughtily, her nose up in the air.

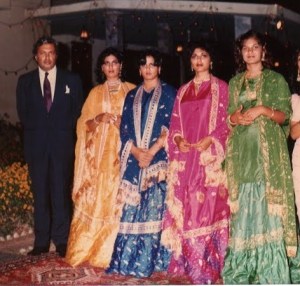

She selected a red and gold brocade sari, a pair of black evening shoes, and a matching hand bag. “Fold the sari nicely and put it in the suitcase with the other things,” she directed me.

My parents voted for Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election, the first US presidential election in which they could vote. They had been naturalized as US citizens the year before in 1979, the same year as the Iranian Revolution which deposed the Shah. Later that same year, 53 Americans were taken hostage for 444 days, from November 4, 1979 to January 20, 1981, symbolically released the same day Reagan was inaugurated into office.

When the hostages were taken, Puchi and I were living in Pakistan, attending the International School of Islamabad. The superintendent of our school, a man by the name of William Keough, had previously been the superintendent of the American School in Tehran. After the Iranian Revolution, he was posted to the International School in Islamabad. That November, Mr. Keough returned to Tehran to finish up business and pack the last of his things, and was taken hostage with the other Americans on November 4.

Anti-Americanism was spreading through Central and South Asia, and the American embassy in Islamabad was also attacked later that November, the same day that Puchi and I were to fly to Karachi on our way to Connecticut for the Thanksgiving holiday. The previous month, in October, we received a telex, to my great joy, “You are cordially invited to 112 Stoner Drive for Thanksgiving Dinner.” I thought my parents were responding to the misery I often expressed about having to live in Pakistan during my junior high school years, but in actuality, our names had come up for US citizenship and we returned to Connecticut for the Naturalization Oath Ceremony just as the Americans were being evacuated from Pakistan.

Before Reagan won the Republican presidential primary, my mother was keen on George H. W. Bush. She supported the elder Bush in the primaries and even hosted a fundraiser for him at our home in Connecticut. She was active in the West Hartford Republican Women’s Club.

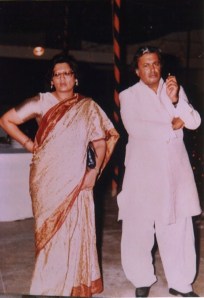

I wasn’t home the day George Bush came over for the fundraiser, but I remember a photo of Mimo, dressed in a blue shalwar kameez, shaking his hand.

My mother never received a formal invitation to the White House, but I know she enjoyed the inauguration.

Eight years later in 1988, I cast my ballot for George H. W. Bush in the first presidential election in which I could vote. My family was Republican and I was comfortably following in their foot steps. I was towing the party line. As I became more politicized in later years, I changed my party affiliation, but I always like to tell people that I voted for Bush in 1988. It just goes to show you, a person really can change.