I have an irrational fear of fish. I like eating fish, I just don’t like swimming with them. This means I am most comfortable in a swimming pool, and most uncomfortable in any kind of water that is home to living creatures. Ponds and lakes are the worst in my opinion, followed by rivers and oceans.

I like to swim, and I like the ocean but swimming in the ocean can stress me out. For years I tried to hide this fact from most people. “Let’s go swimming!” my friends would say running into the ocean.

“I’m right behind you!” I’d yell. “I just want to get a little more sun.” This would buy me some time and if I was lucky, they’d be back before I would have to go in. Otherwise, I would reluctantly go into the ocean, but I was always twitching and turning. “Was that a fish that just brushed up against my leg?”

With my family, I was more transparent about my fear of swimming in the ocean. We would often take our winter holidays near the beach. In early December of 1983 I wrote my father a letter from boarding school in Connecticut. He was in Pakistan. “I think we’re going to Panama for Christmas break. I’m not too keen on it, but it will be okay.”

One of our cousins was living in Panama City with her husband and children, and my mother arranged a trip for us to visit them and other parts of Panama over the winter holiday. Puchi, Mimo, and I packed our bathing suits and beachwear and left for Panama with our mother in late December. Our friends Peter and Joel joined us for parts of the trip.

Earlier that year, in August of 1983, Manuel Noriega had assumed power of Panama, promoting himself to General and becoming the military dictator until 1989 when the US invaded Panama, removed him from power, and tried him for drug trafficking, racketeering, and money-laundering.

While he was in power, Noriega was on the CIA payroll, and for much of the 1980s, he extended new rights to the US. Despite the canal treaties, he allowed the US government to set up listening posts in Panama which allowed the US to monitor sensitive communications in all of Central America and beyond. Noriega also aided the US-backed guerrillas in Nicaragua by acting as a conduit for US money, and according to some accounts, weapons. Noriega had been on the CIA’s payroll off and on since the 1950s, but towards the late 1980s, the US viewed him as a double agent believing that he was providing information not only to the US and its allies Taiwan and Israel, but also to communist Cuba.

The 1988 Senate Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics and International Operations concluded that “the saga of Panama’s General Manuel Antonio Noriega represents one of the most serious foreign policy failures for the United States. Throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, Noriega was able to manipulate US policy toward his country, while skillfully accumulating near-absolute power in Panama. It is clear that each US government agency which had a relationship with Noriega turned a blind eye to his corruption and drug dealing, even as he was emerging as a key player on behalf of the Medellin Cartel.”

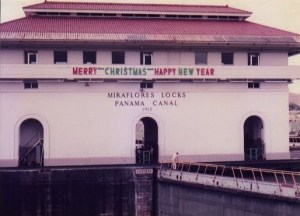

The Panama Canal, 1983

“Didn’t you say one of your classmates lives in Panama City?” my mother said after we arrived. “Ring her up.” My mother loved meeting new people and she’d rather have a local perspective than a tourist one. I didn’t want to impose on my friend’s winter holiday, but it was impossible to say no to my mother, so I reluctantly called my friend.

As it turned out, my friend’s mother was Noriega’s personal secretary and my cousin’s husband was a branch officer for BCCI, the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, providing personal banking services for Noriega. He later became embroiled in the BCCI scandal and would later be convicted for the money-laundering services he provided for Noriega. I wasn’t aware of the nuances of these political connections back then, I just remember we had a pretty good vacation, later realizing these ties to Noriega probably were partly the reason for the decadence we experienced.

For instance, in passing, we mentioned we might like to visit the San Blas Islands, an archipelago of 365 islands off the north coast of the Isthmus, the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean linking North and South America, east of the Panama Canal. The next thing we knew, a private plane was arranged. When we got to the small airport, there were seven of us and only six seats on the plane. Within moments, a new plane that could accommodate our party of seven arrived on the tarmac.

The San Blas islands were beautiful. For lunch we ordered fish, and the restaurant staff asked us to select one to our liking, pointing to a netted part of the sea where the fish identified for the restaurant kitchen were swimming in isolation. I was glad not to be swimming with the fish, especially since I was about to eat one of them.

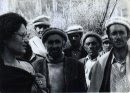

The Kuna Indians of the San Blas Islands

We also went to Taboga, a small beach resort, as well as the Panama Canal, and after Joel and Peter left, the four of us went to Conta Dora. My friend’s mother said they would be visiting the same resort and invited us to lunch. We arrived at the hotel restaurant and thought we must have the wrong day or the wrong restaurant. “The restaurant is reserved for a private party,” the Maitre D’ informed us. There was one long, elaborate, U-shaped table set up in the middle of the outdoor veranda.

“We must have the days mixed up,” one of us said. “There must be some important people coming for this luncheon,” we predicted. It turned out, we were the guests of honor. My friend’s mother had arranged the luncheon for us.

The view from the hotel restaurant in Conta Dora.

When we arrived at the resort a day or two earlier, I went to the room I shared with my mother, changed into my bathing suit, and announced that I was going to be spending the rest of the day by the pool.

“Have you seen the water?” one of my sister’s said. “It’s beautiful. Clear and blue. Why would you want to go to the pool?”

“She doesn’t like to swim with the fish,” my mother reminded them.

The beautiful Sea, in which I did not swim.

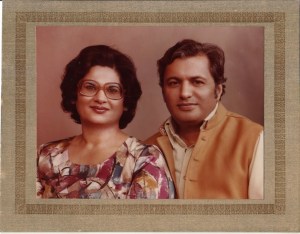

My mother looking relaxed in Taboga.